A Legacy begun by the Medici Family

The Italian name of this museum literally translates into “Workshop of semi-precious stones”, however, the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (also known as OPD) has become to mean so much more to the world of art than simply a showcase for objects made from stone.

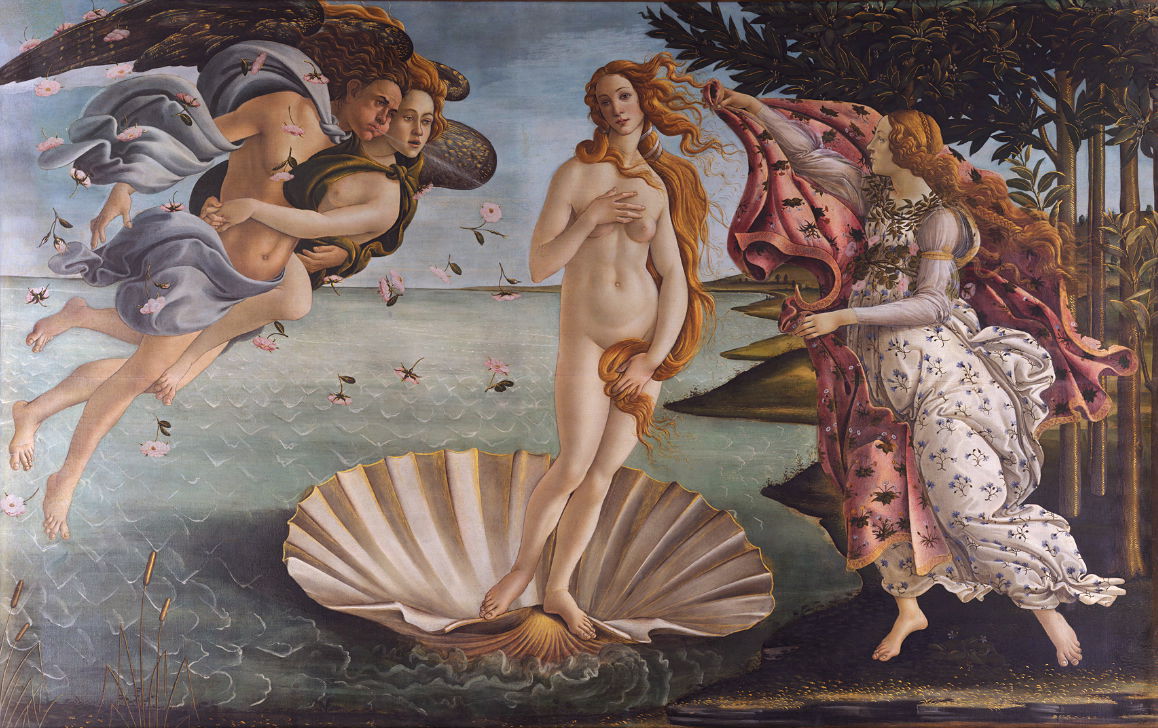

The art of marble-inlay existed long before 1588 when Grand Duke Ferdinando I de' Medici established a court-funded laboratory specializing in semi-precious mosaic work and inlays. The type of work was exalted during the decoration of the Cappella dei Principi (the Chapel of the Princes) in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, the Medici family's final resting place.

What is Commesso Fiorentino?

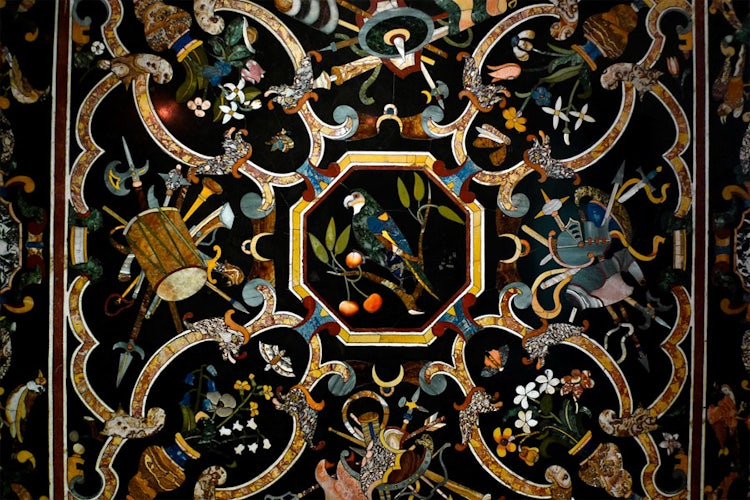

It is the piecing together of marble using different shapes and colors to create a mosaic image or a decorative design. This art grew in popularity and is definitely a product of Florence and a family tradition today carried on by few, for example, the Fratelli Traversari & Renzo e Leonardo Scarpelli.Workshop of Semi-Precious Stones

This Grand Ducal institution has remained active for more than three centuries and has served as the core of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure collection on display. Yet over time, with the changing tastes in art and architectural decoration, the workshop found itself transforming and taking on the role of a restoration laboratory.

Today, the institution is an autonomous part of the Institute of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage, “whose operational, research and training activities find expression in the field of conservation of works of art.”

The OPD was fundamental during the Flood of 1966 and is considered one of the premier restoration workshops in the world - not just for stone inlay but an innovative and cutting edge point of reference for a plethora of material.

Their expertise stretches from tapestry and carpets, archaeological finds, bronze pieces and sculpture, weapons, as well as armory and painted furniture. It also extends to paper and parchment materials, stone, gold, wooden sculptures, terracotta, textiles and, of course, the conservation of mosaics and semiprecious stones.

What will you see inside the museum

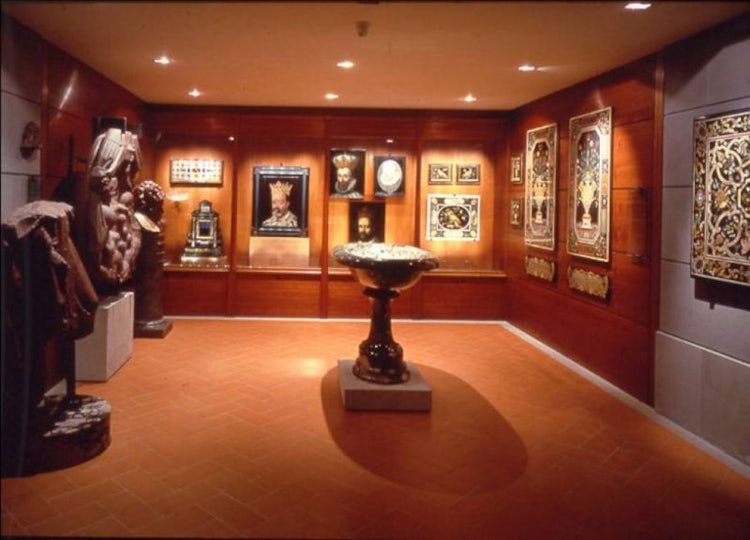

The general organization of the museum was renovated in 1995, and the collection was rearranged according to themes, following the progression of "commesso fiorentino", featuring both its production and physical aspect. The offices also do quite a bit of restoration on-site as well as at several different branch offices, but that work is not open to the general public. It is possible to visit the workshops with a guided tour.

As you walk around the museum, you will find a room documenting the works produced during various periods, starting with the Medici family up until the mid-1800s. On the upper floors in the mezzanine, space is dedicated to the craftsman’s techniques and includes a rich set of stone samples, workbenches, tools, and examples of a few of the production phases of intarsia and inlay work.

The museum is small and in approximately one hour you can visit the entire structure. The size in no way takes away from the intriguing mix of art and technique, especially interesting for those who admire stones, their color, and vibrancy and the expressive nature within the art of commesso fiorentino.

The ground floor of the museum is divided into seven general areas and will take you on a small journey of how this art transformed and grew over the years.

→ The first portion displays Cosimo I’s curiosity and passion for archaeological marbles and some beautiful examples of artwork which competed with paintings and sculpture.

→ The construction of the grand funerary chapel of the Medici family in San Lorenzo was begun by Ferdinand I in 1604 and there is a section in the museum dedicated to the unused designs and decorative elements of the work, such as the panels from the imposing 17th-century altar.

→ Next, you will be introduced to the production phase which used flower and still life compositions as their inspiration, generally on a black background so as to fully enhance the brilliant color range of the flowers and birds. This technique was widely adopted in furniture decoration.

→ You will then find examples of the sculptor Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652-1725) and a semiprecious stone cutter, Giuseppe Antonio Torricelli, who took this art to a new level combining techniques and expression.

→ Not only the Medici family but also the Hapsburg-Lorraine Grand Dukes (1737) worked with goldsmiths and engravers, modifying the traditional naturalistic motifs on a black ground and replacing them with landscapes and genre scenes, based on designs by Giuseppe Zocchi.

→ There is a small section dedicated to “scagliola” a technique which imitates the stone intarsia work but is far more complex (in photo above).

Scagliola consists of pouring variously coloured liquid gesso into a hollowed cavity in a previously prepared gesso layer. The final polishing of the composition with the aid of animal glue confers an aspect similar to stone inlay work.

→ The last section starts at the end of the reign of the Grand Dukes in 1859, which despite attempts to meet the changing taste of a new age under the supervision of the painter Edoardo Marchionni, found the OPD looking towards new outlets in the field of restoration.

Upstairs, there is a display of the various types of stones, with their scientific names and an indication of where they could be found worldwide. In addition to all the color, you will find several examples of equipment used to cut and piece the marble together both in the creation of a new piece and during restoration.

Restoration

The areas dedicated to restoration are spread throughout the city, depending on the type of material and space required. As you peek through the wrought iron gate that looks out over the courtyard, you will catch glimpses of pieces awaiting their turn. However, these workshops are not open to the public except upon request or a privately organized tour. The Opificio delle Pietre Dure's restoration teams are almost always on the list of any restorations being done across the city, from sculpture to paintings to tapestries. If you want to see something truly unique, I highly recommend booking a tour of one of those laboratories (for private groups, currently suspended because of Covid-19.

This museum details a type of artwork that has grown with Florence's demand for new artistic outlets. Though rarely exalted on its own, everywhere you look in churches, historic palaces and even in architecture, you will find traces of this precise and intricate skill. The museum is small yet intriguing, especially on a day when you have just a bit of time to see something new and different.